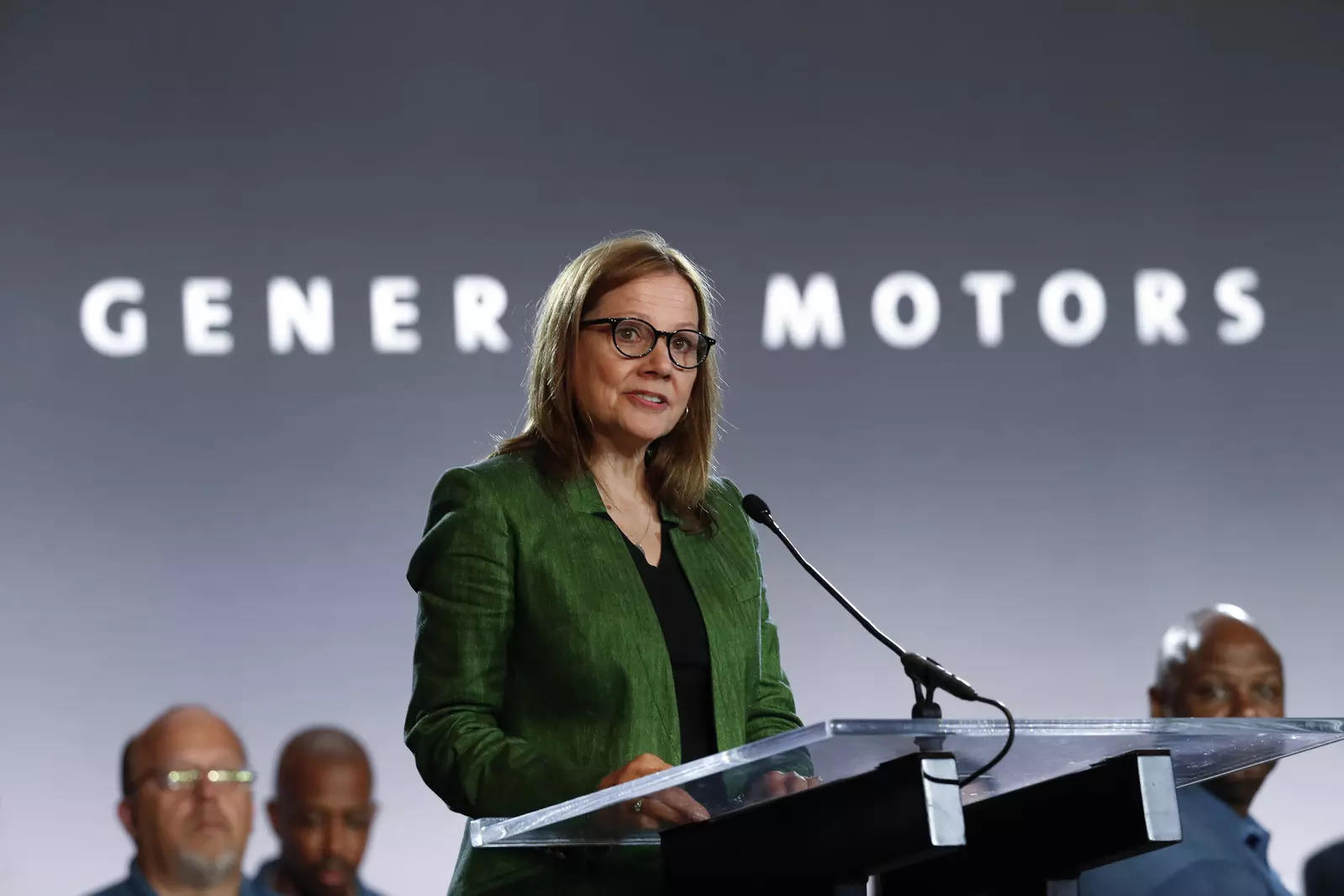

When Mary Barra casually mentioned "diversifying battery chemistry" during GM's Q1 2025 earnings call, it might have sounded like typical corporate speak. But beneath that innocuous phrase lies a seismic shift in General Motors' electric vehicle strategy, one that will fundamentally change which EVs Americans can afford and where they're built.

Multiple sources confirm GM is preparing to introduce lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries to its Ultium platform, a move that could finally deliver the long-promised "$30,000 EV" while dramatically reshaping the company's manufacturing footprint.

GM is working with LG Energy Solution (LGES) and Samsung SDI to install LFP battery production lines at their joint venture plants in the United States. The company aims to reduce costs and offer a broader range of battery options for its electric vehicles (EVs).

GM plans to use LFP batteries in five of its seven existing EV models, including the Chevrolet Bolt, Equinox, Blazer, and Silverado EV. These batteries are expected to be cheaper than nickel-rich alternatives, which should make EVs more affordable for mass-market consumers. The implications of this chemistry switch extend far beyond technical specifications.

By adopting LFP technology—already used successfully by Tesla and Chinese automakers—GM is preparing to launch a second wave of affordable EVs that could finally achieve price parity with gas-powered vehicles.

The 2025 Chevy Bolt's surprise return at "lower-than-projected cost," as CFO Paul Jacobson noted during the call, provides the first tangible evidence of this strategy in action. Industry analysts now believe the Bolt's revival only makes financial sense if it's using LFP cells rather than the nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM) chemistry found in current Ultium vehicles.

The CATL Connection

GM's path to LFP adoption runs through a quiet partnership with Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Limited (CATL), the Chinese battery giant that supplies LFP cells to Tesla.

While neither company has publicly confirmed the arrangement, supply chain documents reveal GM has been securing LFP battery materials through CATL's new Mexican operations, a clever workaround that qualifies the cells for U.S. EV subsidies while avoiding direct imports from China.

This parallel supply chain explains several recent mysteries in GM's operations:

Why the company suddenly expanded its Ramos Arizpe, Mexico plant's battery capacity

The unexpected cost reductions in GM's 2025 EV production forecasts

How the automaker plans to hit its target of "substantially improving battery costs per kilowatt-hour" by 2026

The CATL deal mirrors Tesla's successful LFP strategy, which allowed the Texas-based automaker to offer lower-priced Model 3 variants while maintaining healthy margins. But GM appears to be going a step further by integrating LFP chemistry directly into its Ultium architecture, something no legacy automaker has yet accomplished at scale.

The End Of The 'Low-End Ultium' Dream

GM's LFP shift effectively kills plans for budget Ultium EVs using traditional lithium-ion chemistry. Previous roadmaps suggested the company would create cheaper versions of its Ultium-based vehicles by reducing battery size or using lower-grade NCM cells.

Instead, GM now appears committed to using LFP for all entry-level models while reserving more energy-dense (and expensive) NCM batteries for premium vehicles like the Cadillac Lyriq and GMC Hummer EV.

This bifurcated strategy carries significant implications:

- Price Cuts Coming: The Equinox EV, currently starting at $34,995, could see its base price drop below $30,000 by 2026 as LFP cells arrive

- Range Trade-Offs: LFP batteries typically offer 10-15% less energy density, meaning base models may have slightly reduced range compared to current projections

- Charging Improvements: Modern LFP chemistry charges faster in cold weather and suffers less degradation, advantages GM will likely highlight

The Geopolitical Tightrope

Tesla Model 3 LFP battery source.

GM's battery chemistry pivot doesn't come without risks. The company must carefully navigate growing tensions between the U.S. and China while maintaining its eligibility for Inflation Reduction Act subsidies.

By working with CATL's Mexican subsidiary rather than importing directly from China, GM appears to have found a viable middle ground, but this arrangement could face scrutiny as Washington grows increasingly wary of Chinese influence in North American manufacturing.

Meanwhile, in light of the United Auto Workers (UAW) union’s broader concerns about battery plant labor conditions, wages, and safety issues at GM's Ultium battery facilities, it stands to reason that the union is equally concerned about GM's growing Mexican battery operations.

It has been involved in negotiations regarding unionizing battery plants and ensuring fair labor practices. While LFP production requires fewer specialized workers than NCM battery manufacturing—potentially making U.S. plants less competitive—GM has committed to maintaining domestic battery production for its premium vehicles

The Bottom Line

Barra's offhand comment about battery chemistry diversification reveals a fundamental rethinking of GM's EV strategy. Embracing LFP technology through its CATL partnership allows the automaker to position itself to finally deliver affordable electric vehicles at scale, while avoiding the margin-crushing price wars that have plagued the entry-level EV market.

The coming year will prove decisive. If GM can successfully integrate LFP into Ultium while maintaining its subsidy qualifications, it may have found the elusive formula for profitable mass-market EVs. If not, the company risks falling further behind Tesla and Chinese automakers in the race to electrify mainstream America.

One takeaway is that the age of one-size-fits-all battery strategies is over. GM's future will be powered by multiple chemistries, each optimized for different vehicles and price points. In this new era, flexibility may prove more valuable than raw energy density.