For over a century, the automobile has represented freedom, power, and the thrill of mechanical mastery. The connection between driver, machine, and road defined what it meant to own and love a car. But in today’s digital era, a different trend is unfolding. Cars are no longer just machines designed to take us from point A to point B. Increasingly, they resemble something else entirely: smartphones on wheels.

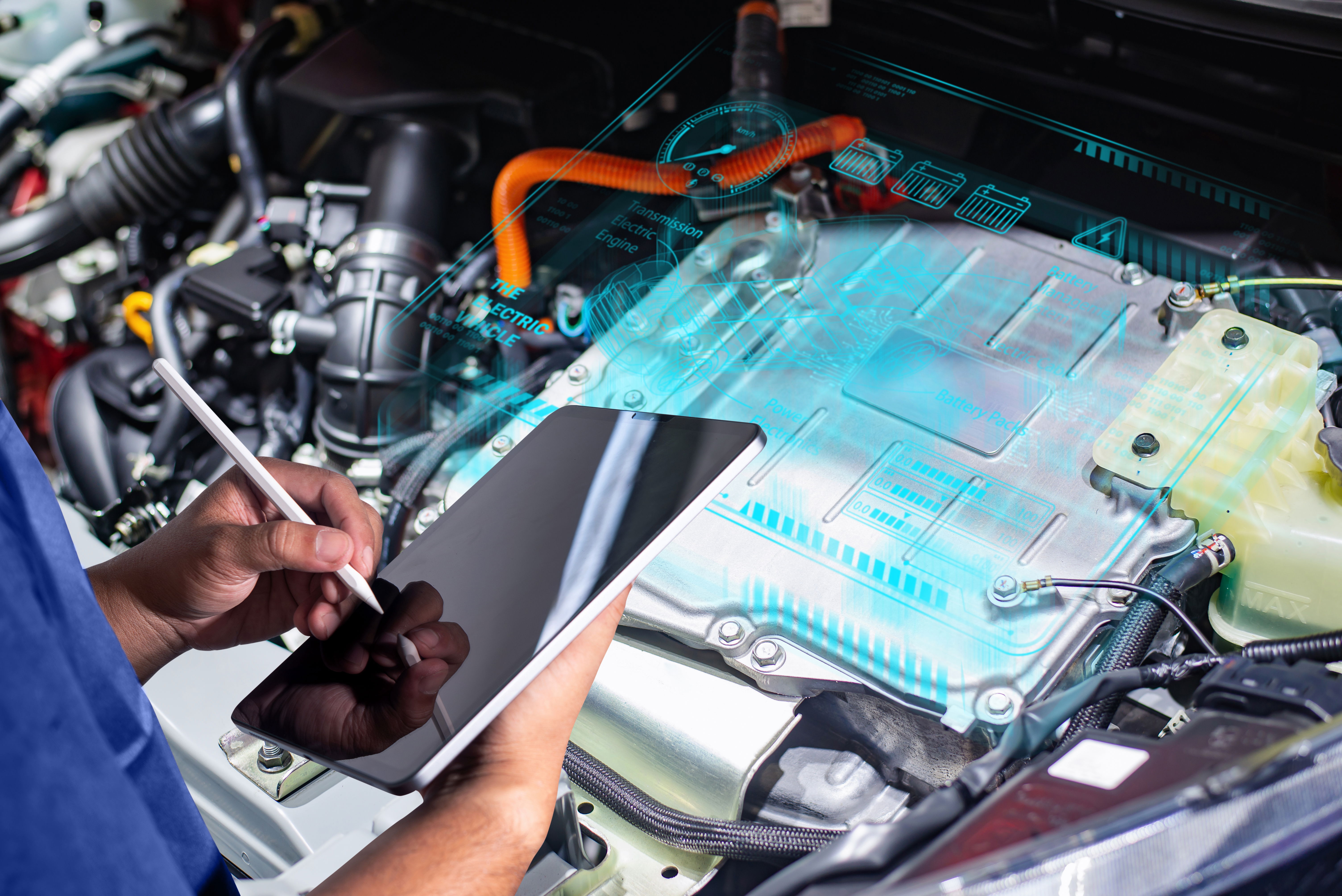

From over-the-air (OTA) software updates to app-based ecosystems and always-on connectivity, automakers are racing to transform cars into rolling tech platforms. This raises a provocative question: in our pursuit of digital convenience, are we losing the soul of driving and settling into the role of beta testers for the auto industry’s software ambitions?

Call this a think piece if you will; let's unpack the smartphone–car parallels, explore how technology is reshaping our relationship with vehicles, and debate whether this shift represents progress—or the slow death of driving passion.

The Smartphone Playbook Hits the Road

When Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone in 2007, he didn’t just change the phone market; he altered consumer expectations forever. Phones became portals to ecosystems of apps, updates, and services. Now, cars are following the same trajectory.

Over-the-Air Updates (OTA)

Just like your phone’s operating system, modern cars can now receive software updates remotely. Tesla pioneered this model, pushing fixes and new features straight to vehicles overnight. Rivals like Ford (with its Power-Up updates), Mercedes-Benz, and even Hyundai now offer similar functionality. Need better battery management, improved autonomous functions, or a new infotainment interface? Just wait for the download.

App Ecosystems

In smartphones, apps redefined what a device could do. Similarly, cars are inching toward app ecosystems. Mercedes’ MBUX system, GM’s partnership with Google, and BMW’s subscription-based feature model are prime examples. Want heated seats, enhanced navigation, or an in-car karaoke app? That could be just another in-app purchase away.

Constant Connectivity

With embedded 5G modems, cars are now always online. This connectivity enables real-time traffic updates, vehicle-to-vehicle communication, and even cloud-based gaming. Automakers see subscription services—from entertainment to performance boosts—as recurring revenue streams.

The similarities are uncanny. Just as smartphones morphed into lifestyle hubs rather than mere communication devices, cars are shifting from transportation tools to mobile platforms designed to keep you plugged in.

Drivers or Beta Testers?

While this technological transformation is dazzling, it also comes with an uncomfortable reality: consumers increasingly serve as beta testers.

Bugs on Wheels: Owners have reported everything from infotainment crashes to phantom braking in vehicles loaded with driver-assistance tech. These aren’t isolated glitches; they’re systemic issues tied to software-centric cars.

Unfinished Products: Tesla’s Full Self-Driving beta is perhaps the most controversial example. Customers pay thousands of dollars for a feature that remains in perpetual testing, raising ethical and safety questions.

Subscription Fatigue: Imagine buying a $70,000 car only to learn that heated seats or extra horsepower require monthly payments. The shift toward “features-as-a-service” feels uncomfortably similar to the nickel-and-diming strategies of smartphone app developers.

Cars are no longer static products perfected in the factory. They’re dynamic platforms evolving on the road—but that also means drivers are living with unfinished, sometimes faulty, experiments.

The Soul of Driving Under Siege

For purists, this digital pivot is eroding what made cars magical in the first place.

Analog gauges, mechanical feedback, and tactile buttons are giving way to digital displays and haptic touchscreens. What was once a visceral, sensory experience is now a glass-panel interaction.

Features like adaptive cruise control, lane-keeping assist, and self-parking diminish the driver’s role. The machine increasingly takes over tasks once seen as integral to the art of driving.

Car enthusiasts argue that passion for vehicles was built on sound, vibration, and connection. When your vehicle becomes indistinguishable from a giant gadget, does it still stir the soul in the same way?

Consider the Porsche 911 versus Tesla’s Model 3. One is engineered to ignite visceral passion through its roar and handling finesse. The other delivers silent, software-driven efficiency. Both represent excellence, but one appeals to the heart while the other appeals to the head. The question is: can software ever replicate soul?

The Case for Progress

Of course, not all is doom and gloom. Advocates of the smartphone-on-wheels model highlight undeniable benefits:

Continuous Improvement

OTA updates mean cars get better over time. Bug fixes, new safety features, and even performance upgrades can extend a vehicle’s relevance long after purchase.

Safety Enhancements

Advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS) have the potential to save thousands of lives by mitigating human error—the leading cause of accidents.

Customization

Just as your smartphone reflects your identity through apps and settings, cars can now be tailored to personal preferences, from digital themes to driving dynamics.

Efficiency

Digital platforms allow automakers to diagnose problems remotely, reducing the need for service center visits and improving uptime for drivers.

Environmental Benefits

Software optimization can improve EV battery efficiency and reduce energy consumption, furthering sustainability goals.

There’s also an argument that younger generations—raised on screens and apps—value convenience over analog romance. For them, the car-as-smartphone model isn’t a dilution of the driving experience; it’s a natural extension of the digital lifestyles they already embrace.

A Battle of Two Philosophies

What we’re witnessing is a clash of two automotive philosophies:

- The Traditionalists: For these enthusiasts, cars should remain machines first and gadgets second. They cherish manual transmissions, steering feel, and the raw connection between driver and machine.

- The Futurists: For this camp, the car’s role is evolving. They argue that clinging to old ideals is nostalgia-driven and impractical. Cars should be safer, smarter, and integrated into the digital ecosystem—even if that means sacrificing some “soul.”

Both sides raise valid points, but the tension highlights an identity crisis: what is a car in the 21st century?

The Dystopian Possibility

The smartphone analogy also invites more sobering speculation. Firstly, planned obsolescence.

Just as smartphones often feel outdated after a few years, will cars become obsolete not because of mechanical failure, but because software support ends? Look what happened to the Fisker Ocean.

After Fisker filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in June 2024, Ocean owners were left stranded—not because their cars broke down mechanically, but because software support vanished. Connected services were cut off, including navigation, remote access, and streaming. Over-the-air updates stopped, leaving critical bugs and even safety recalls unresolved. Owners lost access to Fisker’s cloud, meaning no diagnostics, no feature upgrades, and no way to fix software glitches

A company called American Lease tried to salvage the situation by buying leftover Oceans and securing software rights. They even struck a deal with the Fisker Owners Association (FOA) to keep the cars online. But:

- FOA couldn’t meet payment deadlines

- American Lease withheld access to the software and cloud services

- The partnership collapsed, leaving owners with expensive EVs that were essentially bricked in terms of digital functionality

Cars are now data goldmines, tracking everything from location to driving habits. Who owns this data, and how is it used? Automakers see dollar signs, but privacy advocates see red flags. Look what happened with GM.

General Motors (GM) was caught selling detailed driver data to third-party brokers like LexisNexis and Verisk. These brokers then resold the data to insurance companies, who used it to adjust premiums based on driving behavior—even if the driver had no history of accidents.

After public outcry and investigative reporting, GM announced it had discontinued the Smart Driver data-sharing program as of March 2024, citing customer trust concerns.

Imagine paying not just for fuel or electricity but also for monthly “access” to basic car functions. This future feels uncomfortably plausible. With automakers pushing toward shared mobility and subscription models, the idea of truly “owning” a car may fade, replaced by a relationship akin to leasing your smartphone.

If these trends accelerate unchecked, cars could become disposable, profit-driven tech products—far removed from the durable machines many of us grew up with.

Searching for Balance

The future doesn’t have to be all-or-nothing. There are ways to integrate digital convenience without extinguishing the soul of driving.

Some automakers, like Mazda and Porsche, strive to maintain tactile controls alongside digital features, respecting both tradition and innovation. Driver-assist systems can serve as optional aids rather than replacements for skill, ensuring autonomy doesn’t erase engagement.

Clear policies on data ownership, subscription models, and software support could prevent dystopian abuses. Just as vinyl records coexist with Spotify, enthusiast-focused cars could thrive alongside tech-heavy models, catering to diverse consumer desires.

Ultimately, the solution lies in balance—embracing the benefits of connected mobility while safeguarding the qualities that make cars more than just tools.

So, Where Do We Go From Here?

Cars as smartphones on wheels are both a marvel and a warning. On one hand, digital platforms promise unprecedented safety, efficiency, and personalization. On the other, they risk turning vehicles into soulless gadgets that prioritize subscriptions over sensations. The auto industry’s trajectory reflects broader societal shifts: convenience over craftsmanship, connectivity over individuality, data over privacy.

The danger is that in our rush to embrace cars as rolling tech ecosystems, we may forget why we fell in love with driving in the first place. So, are cars just becoming giant smartphones on wheels? In many ways, yes. The more pressing question is whether we—drivers, enthusiasts, and consumers—will demand that the soul of driving remain part of the equation. If we don’t, the romance of the open road may soon be replaced by the sterile glow of a dashboard screen.