In an airy hangar in Stratford, Connecticut, something unusual is taking shape. Not quite a helicopter, not quite a fixed-wing aircraft — but something in between, hovering on the edge of aviation’s next frontier. This is the Nomad family of drones from Sikorsky, the storied rotorcraft maker now part of Lockheed Martin, and it may very well spell a turning point in uncrewed aerial systems.

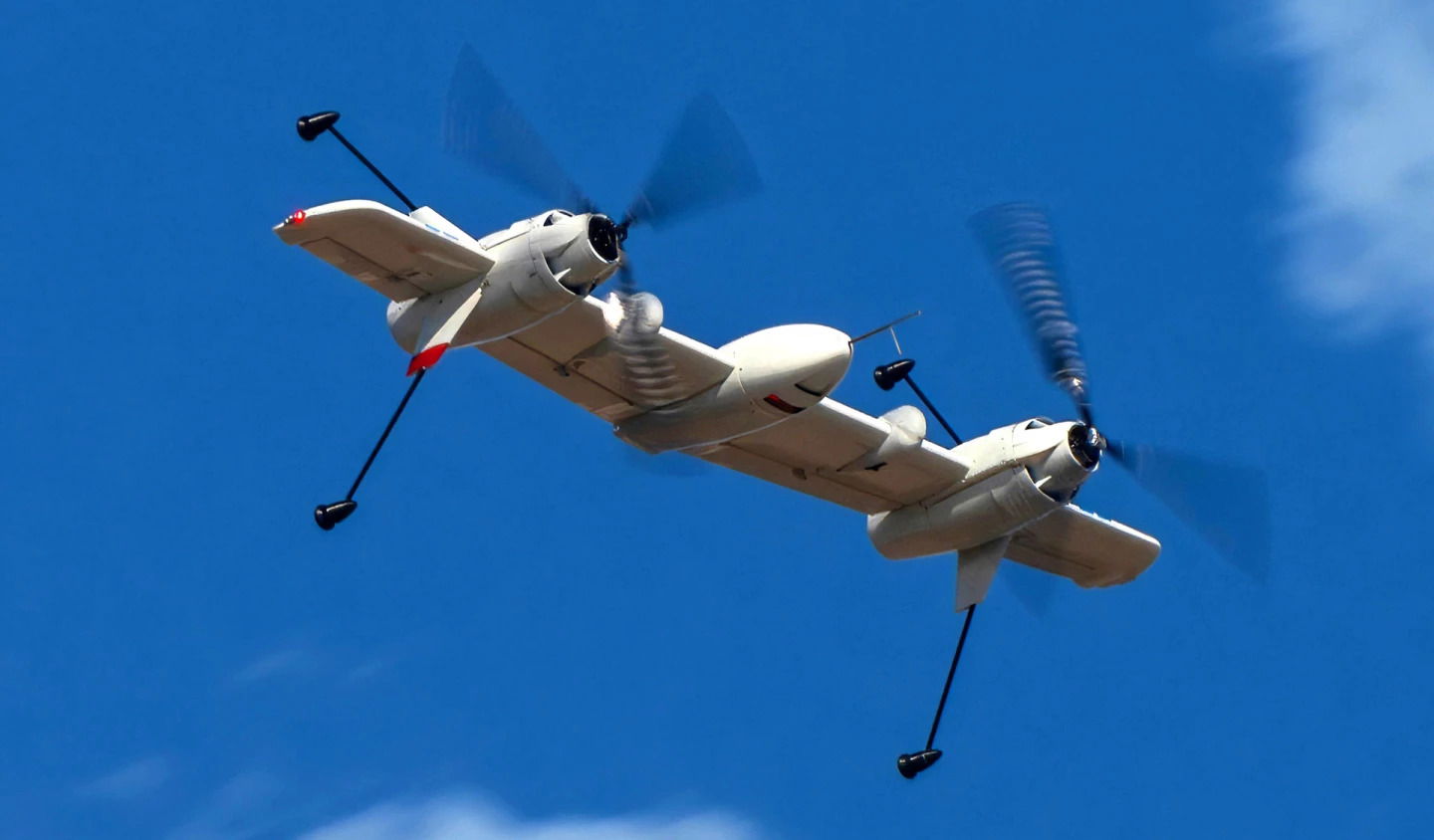

At the heart of the Nomad’s innovation lies a deceptively simple idea: the rotor-blown wing. In this configuration, twin rotors mounted on a long wing generate a powerful airflow that is directed over the wing’s surface, creating additional lift during vertical takeoff and landing. The genius is that, during hover and transition phases, the wing is not just a passive structure — it becomes an active lift generator. Then, as the Nomad transitions to forward flight, the wing takes over, delivering the efficiency and endurance of a fixed-wing design.

What results is a hybrid UAS (uncrewed aerial system) with the runway independence of a helicopter and the range, speed, and fuel economy of an airplane. And Sikorsky isn’t just building one prototype — it’s building a family.

Scaling from Pocket Drone to Black Hawk Sized Platform

Sikorsky’s vision for Nomad spans a remarkably broad spectrum. The company has defined a family that covers Group 3 drones (relatively small) all the way up to Group 4–5 airframes, comparable in footprint to a Black Hawk helicopter.

The smallest demonstrator, the Nomad 50, has a wingspan of just 10.3 feet (3.14 m) and weighs around 115 pounds (52 kg). It has already undergone extended flight testing.

In parallel, Sikorsky is building the Nomad 100, a Group 3 drone with an 18-foot (5.5 m) wingspan, expected to make its first flight soon.

Beyond that, the company plans larger variants — scaled-up versions — that could carry heavier payloads, undertake more demanding missions, and more closely resemble traditional medium-lift helicopters in size.

But it’s not just about clever aerodynamics. The Nomad family is deeply integrated with MATRIX, Sikorsky’s digital co-pilot and autonomy suite. Developed in collaboration with DARPA, MATRIX offers full autonomy: it can handle everything from takeoff to landing, including obstacle avoidance, threat evasion, and even complex mission planning.

This is a game-changer. With advanced autonomy in place, a Nomad doesn’t need to be manually flown; it can carry out highly demanding tasks with minimal human intervention, freeing operators to focus on strategic decisions rather than piloting. The system’s open architecture also ensures it can communicate and operate alongside fixed-wing and rotor-wing manned aircraft.

Propulsion: Hybrid-Electric for the Small, Conventional for the Large

Sikorsky is also adopting a hybrid-electric propulsion strategy for the Nomad family. The smaller variants like the Nomad 50 and 100 rely on hybrid-electric drivetrains, maximizing efficiency, reducing fuel consumption, and enabling long endurance.

On the other hand, the larger Nomads (those in Group 4–5) will use more conventional engines. This choice reflects the balance between efficiency and raw power: the hybrid-electric system works well for lighter systems, while heavier platforms benefit from mature, high-thrust conventional propulsion.

Sikorsky designed the Nomad not just as a niche UAV, but as a multirole family. The company sees it as suited for a sweeping range of missions:

Military tasks: Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance, and Targeting (ISR-T); contested logistics resupply (delivering supplies in contested or denied environments); light attack; maritime patrol; and persistent communications.

Civilian roles: Search & Rescue (SAR), forestry monitoring, firefighting oversight, humanitarian missions, and monitoring pipeline infrastructure.

Because of its VTOL capability and scalability, a Nomad could deploy to remote or dispersed areas — both on land and at sea — without needing runways. That makes it especially useful in scenarios where traditional fixed-wing aircraft are hampered by infrastructure, and helicopters are too vulnerable or inefficient.

To understand the broader impact of Nomad, one must consider how it fits into modern military thinking. Rich Benton, Vice President and General Manager at Sikorsky, described Nomad as a force multiplier.

In contested theaters — for example, in the Indo-Pacific — the ability to deploy ISR, logistics, or light attack platforms from dispersed, austere locations is a powerful strategic advantage. Nomads can operate independently, without needing large support infrastructure.

By complementing existing manned aircraft like the Black Hawk, they can relieve those platforms of some risk, allowing them to focus on high-risk or high-payoff missions while Nomads handle persistent surveillance, supply runs, or communications relay.

The March Toward Autonomy

What’s particularly bold about the Nomad program is how swiftly it has advanced. According to Lockheed Martin, the first extended flight test of the Nomad 50 prototype was completed in March 2025.

Now, with the Nomad 100 under construction and larger variants already on the drawing board, Sikorsky is pushing a rapid-development trajectory. They’re not chasing a one-off drone; they’re building an ecosystem. And that ecosystem, underpinned by MATRIX autonomy, could shift how military and civilian agencies think about UAS deployment.

Of course, this vision is not without risks. Scaling up rotor-blown-wing designs is far from trivial. Larger aircraft require more robust structures, more powerful propulsion, and more sophisticated control systems. Ensuring that the autonomy system performs reliably in contested environments — where electronic warfare, GPS-denial, or physical threats may be present — will be a nontrivial engineering and operational challenge.

Moreover, hybrid-electric systems, while promising, raise questions about energy density, weight, and maintainability. What is the cost per flight hour? How rapidly can these systems scale for operational squadrons? These are open questions that only time — and further testing — will answer.

Still, the Nomad program signals something significant: a shift in how unmanned systems are conceived. Rather than building ever-larger fixed-wing drones or duplicating the helicopter architecture in UAS form, Sikorsky is proposing a hybrid architecture that could truly bridge the gap.

Its strength lies in versatility: an ability to take off and land vertically, to fly efficiently over long distances, to operate autonomously, and to scale from small tactical units to larger strategic platforms. That combination could transform logistics in forward-deployed units, provide persistent ISR from hard-to-reach places, and offer a new tier of airpower that doesn’t require runways.

From a broader perspective, as militaries around the world increasingly emphasize distributed operations, resilience, and autonomous systems, Nomad may be exactly the kind of technology that shifts the balance. It's not about replacing helicopters or manned planes; it's about augmenting them, offering resilience through dispersion, and reducing logistical risk.

So, what’s next for Nomad?

In the short term, the Nomad 100’s maiden flight looms large. That flight will validate not only the aerodynamics of the rotor-blown wing at a larger scale, but also the integration of its hybrid-electric drivetrain and autonomy stack.

If successful, we can expect accelerated development of the Group 4/5 variants — the near–Black Hawk class — potentially fielded for maritime patrol, special-operations logistics, or even light attack roles.

Beyond that lies the real promise: a modular, scalable UAS family that can be adapted for future needs. Whether in the skies over contested ocean regions, in humanitarian operations in remote terrain, or in booming civilian roles like firefighting or medical supply, the Nomad family could become a ubiquitous presence — a flying, autonomous workhorse.