The Great Engine Debate: Why Your Precious 2JZ Won’t Last Like a Small-Block Chevy

The internet loves a good JDM vs. American muscle debate. On one side, you have the die-hard import fans, swearing by the legendary Toyota 2JZ, RB26, and Honda B-series engines. On the other, the old-school gearheads who’ll tell you nothing beats a trusty Chevy 350, Ford 302, or Mopar 318.

Within this dust storm lies an uncomfortable truth: When it comes to real-world, no-nonsense reliability, American V8s wipe the floor with their Japanese counterparts.

Yes, the 2JZ can handle 1,000 hp on stock internals. Yes, the RB26 is a masterpiece of twin-turbo engineering. But let’s be honest—how many of these engines are actually still running strong after 300,000 miles of daily driving, neglect, and abuse? Meanwhile, small-block Chevys and Ford Windsors are still chugging along in work trucks, beat-up hot rods, and farm equipment decades after they left the factory.

That's what we're talking about here. Pure, no-excuse reliability. It's not about dyno numbers or tuner cred but about which engines actually survive in the wild. And by that metric, American muscle wins every time.

See also:

The 300,000-Mile Test: Where JDM Engines Fall Short

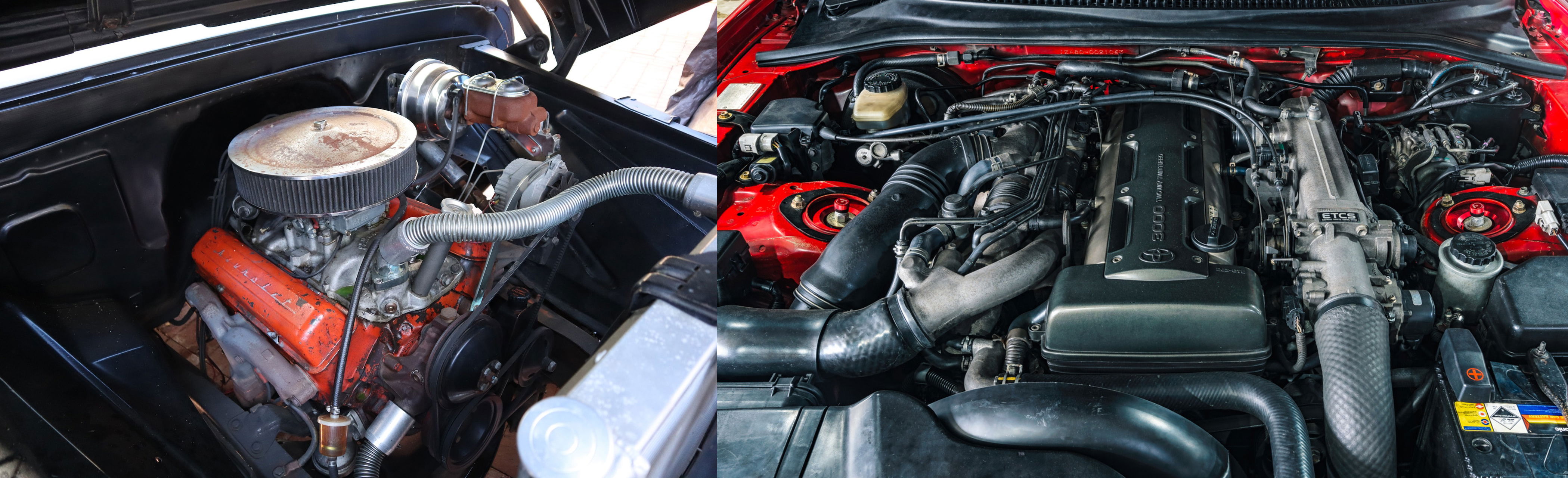

3.0-liter 2JZ from the Supra Aristo.

JDM fanboys love to brag about their engines’ power potential, but let’s talk about something far more important: longevity under real-world conditions.

Take the Toyota 2JZ-GTE, the internet’s favorite inline-six. Sure, it’s strong—but it’s also overengineered in all the wrong ways.

The JDM twin-turbos are more like twin headaches. The sequential turbo system in the Supra is a nightmare to keep running smoothly, and once those ceramic turbines go (and they will go), you’re in for a costly rebuild.

Another weakness is the overcomplicated vacuum systems. The 2JZ relies on a maze of hoses and solenoids just to control boost. One small leak, and suddenly your car runs like garbage.

Have we forgotten the expensive, hard-to-find parts? Try pricing out a replacement head for a 2JZ versus a Chevy 350. One will cost you a few hundred bucks. The other might require a second mortgage.

Now, compare that to a Chevy 350.

It presents none of that nonsense about turbos and variable valve timing. Just a simple pushrod V8 that makes torque where you need it. Parts are everywhere. You can rebuild a small-block Chevy with components from any auto parts store in America.

But the best part is that this perfect representation of American muscle takes abuse like nothing else. Run it low on oil? It’ll keep going. Overheat it? It might warp, but it’ll probably still run. Neglect it for years? It’ll still fire up with fresh gas.

The bottom line is that the 2JZ is a race engine that somehow ended up in a street car. The 350 is a truck engine that just happens to also dominate drag strips. One was built for peak performance. The other was built to last.

The Myth Of Japanese Invincibility

JDM enthusiasts love to claim their engines are "unbreakable," but reality tells a different story.

RB26s eat head gaskets if you look at them wrong. Honda B-series engines spin bearings if you rev them too hard without proper oiling mods. 4G63s crack blocks when pushed beyond stock boost levels.

Meanwhile, a Ford 302 Windsor will happily run on cheap gas, leak oil for 100,000 miles, and still start up every morning.

The clear difference is that American V8s were designed for durability first. They use thick, simple iron blocks that don’t flex under load. They use low-stress, low-RPM powerbands that don’t thrash bearings. They benefit from forged cranks and rods even in factory form.

Japanese engines, for all their brilliance, were often built to peak efficiency rather than brute-force longevity. That’s why you see so many high-mileage LS engines and so few high-mileage 2JZs still on the road.

Summarily, American muscle engines were overbuilt from the factory. Japanese engines were optimized, and optimization often comes at the cost of long-term survival.

See also:

The Aftermarket Advantage: Why American Wins The War Of Attrition

Here’s where the argument gets really one-sided: ease of repair.

If you're unlucky enough to blow a head gasket on a 2JZ, you’re pulling the entire engine just to get to the head bolts. But if you need a new cam for your small-block Chevy, you can swap it in an afternoon without even pulling the radiator.

American V8s were designed to be worked on. Japanese engines were designed to be precise. Guess which one matters more when you’re broke down on the side of the road?

Now, let’s talk about cost.

Let’s peel back the curtain on one of the most glaring differences between American V8s and their JDM counterparts: the financial reality of ownership. The price gap can be catastrophic for anyone who actually plans to drive their car rather than park it on Instagram.

Walk into any U-Pull-It junkyard in America, and you’ll find rows of early-2000s GM trucks with intact 5.3L LS engines. These aren’t rare. They aren’t precious. They’re industrial-grade power units that GM produced by the millions, and that’s precisely why they’re so beautiful. A running 5.3L with harness and ECU can be yours for $300–$800, depending on how dirty your shirt is when you show up to negotiate.

Now, try finding a 2JZ-GTE for less than the price of a used Miata. The last time Toyota installed these in a production car was 2007, and the cult following has turned them into speculative assets rather than drivetrain components.

A clapped-out, non-turbo 2JZ-GE from a Lexus IS300 will gleefully set you back $1,500–$3,000. A GTE with unknown mileage, questionable compression, and "ran when pulled" provenance will easily demand $5,000–$8,000. One that’s actually been refreshed? You might as well be financing a second mortgage.

This isn’t inflation. This is artificial scarcity fueled by hype. The 2JZ was never designed to be a gold-plated unicorn. It was an overbuilt ’90s luxury car motor that happened to respond well to boost. Yet today, you’re paying Porsche tax for what is, at its core, a Toyota engine.

The Aftermarket Domino Effect

The financial hemorrhage doesn’t stop at the engine itself. Every supporting component for a JDM swap carries a "because we can" markup:

- LS swap mounts? $150–$300.

- 2JZ swap mounts? $400–$800.

- LS wiring harness simplification? $200 for a standalone.

- 2JZ harness de-looming? $1,000+ because you need a Mines or Tweak’d ECU to make it run right.

Even routine maintenance becomes a wallet biopsy.

- LS oil pump: $50 (Melling M295).

- 2JZ oil pump: $300 (and you better upgrade it if you’re making power).

The LS ecosystem thrives on industrial ubiquity. The 2JZ ecosystem survives on nostalgia-driven scarcity. One is designed to be serviced by a mechanic in rural Nebraska with a 1/2-inch drive impact. The other requires a specialist in California who charges $180/hr to tell you your VVTi gears are out of sync.

The Disposability Paradox

Here’s where the rubber meets the road (or more accurately, where the rod meets the pavement):

An LS is meant to be used up. When your junkyard 5.3L finally taps out at 450whp on stock internals, you shrug, scrap it for $100, and grab another. The 2JZ’s reputation for indestructibility means every blown example is treated like a fallen comrade, translating to a tragedy requiring a $4,000 rebuild rather than a $400 Craigslist replacement.

This creates perverse incentives. LS owners are free ro drive their cars hard because the consequences are trivial. On the other hand, 2JZ owners baby their investments because failure means financial ruin.

In the end, American V8s actually get enjoyed, while JDM legends become garage queens—not because they’re fragile, but because the financial risk of using them as intended is untenable.

By these metrics, the humble small-block Chevy isn’t just more reliable; it’s the only rational choice for anyone who actually wants to drive rather than worship. The 2JZ is a museum piece. The LS is a tool. And in the real world, tools outlive trophies every time.

The Verdict: Power vs. Permanence

If you want maximum horsepower on a dyno sheet, sure, go JDM. But if you want an engine that starts every morning for 30 years, you want American iron.

The 2JZ is a thoroughbred racehorse—fast, but fragile. The Chevy 350 is a mule—slow, steady, and impossible to kill.

And in the real world? Mules outlast racehorses every time.