The Cars That Jumped the Gun: 20 Brilliant Ideas That Came Too Soon

What if the automotive world had taken a radical detour? Hidden in the archives of history lie forgotten prototypes so revolutionary, they could have rewritten the rules of transportation.

From nuclear-powered sedans to turbine-engine coupes and hovering dream machines, these were the cars that dared to leap decades ahead only to vanish into obscurity. Some were too advanced for their time. Others fell victim to corporate cold feet, technological limits, or sheer bad luck.

But their legacy lingers in today’s EVs, autonomous tech, and hyper-efficient designs. This is the story of twenty groundbreaking concepts that promised to change everything… and why we’re still catching up to their vision.

Tucker 48 "Torpedo" (1948) – The Safety Revolution That Was Too Soon

Why it mattered: Preston Tucker’s 1948 sedan was packed with innovations like a rear-mounted flat-six engine, disc brakes, a padded dashboard, a pop-out windshield (for crash safety), and a center "Cyclops" headlight that turned with the steering wheel. It was one of the first cars designed with occupant safety as a priority.

Why it failed: Political pressure, SEC investigations, and accusations of fraud (later debunked) tanked the company after only 51 cars were built. Detroit’s Big Three saw Tucker as a threat and may have worked to undermine him.

What could have been: If Tucker had succeeded, features like crash protection and rear-engine layouts might have become mainstream decades earlier.

Lancia Stratos Zero (1970) – The Wedge-Shaped Future That Almost Was

Why it mattered: Designed by Marcello Gandini (of Lamborghini Countach fame), the Stratos Zero was a radical wedge-shaped concept with a mid-engine layout and ultra-low profile, previewing the supercar designs of the 1970s and 80s. It was meant to showcase Lancia’s engineering prowess and influence future rally cars.

Why it failed: Lancia focused on the more conventional Stratos HF rally car instead, leaving the Zero as a one-off showpiece.

What could have been: If produced, it could have pushed extreme aerodynamic designs into mainstream sports cars earlier, influencing road-going vehicles beyond just exotics.

GM Ultralite (1992) – The Carbon Fiber Revolution That Fizzled

Why it mattered: This concept car was a 1,400-pound four-seater made almost entirely of carbon fiber, achieving 88 mpg with a tiny three-cylinder engine. It was a precursor to today’s lightweight hypercars (like the McLaren F1) and could have made composites mainstream decades before the BMW i3 or Alfa Romeo 4C.

Why it failed: In the 1990s, carbon fiber was prohibitively expensive, and GM was more interested in SUVs than futuristic efficiency.

What could have been: If GM had pursued mass-production techniques for carbon fiber, the entire industry might have shifted toward lightweight materials much sooner, drastically improving fuel efficiency and performance.

Fiat Turbina (1954) – The Jet-Powered Family Car

Why it mattered: Before Chrysler’s Turbine Car, Fiat built a functional gas turbine-powered sedan that hit 160 mph in testing. It was smooth, quiet, and could run on multiple fuels, offering a glimpse of an alternative to piston engines.

Why it failed: Fuel consumption was terrible at low speeds, and turbo lag made it impractical for city driving. Fiat abandoned turbines by 1956.

What could have been: If turbine tech had been refined, it could have rivaled internal combustion engines, leading to a completely different powertrain evolution.

Citroën Karin (1980) – The Pyramid-Shaped Future of Ergonomics

Why it mattered: This three-seat wedge had a central driving position, a futuristic digital dash, and a steering wheel with integrated controls. This was years before the McLaren F1 or modern hypercars. Its radical design prioritized visibility and ergonomics in ways still not fully explored today.

Why it failed: Too avant-garde for conservative 1980s buyers, and Citroën was in financial trouble at the time.

What could have been: If adopted, its central driving position and control layouts could have reshaped cockpit design, influencing sports cars and even autonomous vehicle interiors.

Briggs & Stratton Hybrid (1980) – The Six-Wheeled, Gas-Electric Oddity

Why it mattered: Decades before the Prius, this experimental sedan featured a parallel hybrid system with a small gasoline engine and electric motor, plus a third axle for stability. It was designed for extreme fuel efficiency (reportedly over 60 mpg) and could have jumpstarted the hybrid revolution.

Why it failed: Briggs & Stratton, known for lawnmower engines, had no auto industry leverage, and the 1980s oil glut killed interest in efficiency.

What could have been: If a major automaker had adopted this tech, hybrids might have dominated by the 1990s instead of the 2000s.

Audi Avus Quattro (1991) – The Aluminum Supercar That Previewed the R8

Why it mattered: This sleek, all-aluminum concept had a W12 engine and a full-spaceframe chassis, foreshadowing Audi’s later use of lightweight materials in the A8 and R8. It also featured active aerodynamics—rare for the early ‘90s.

Why it failed: The W12 wasn’t ready for production, and Audi prioritized sedans over supercars at the time.

What could have been: If Audi had greenlit the Avus, it could have beaten the McLaren F1 to market with an aluminum monocoque supercar.

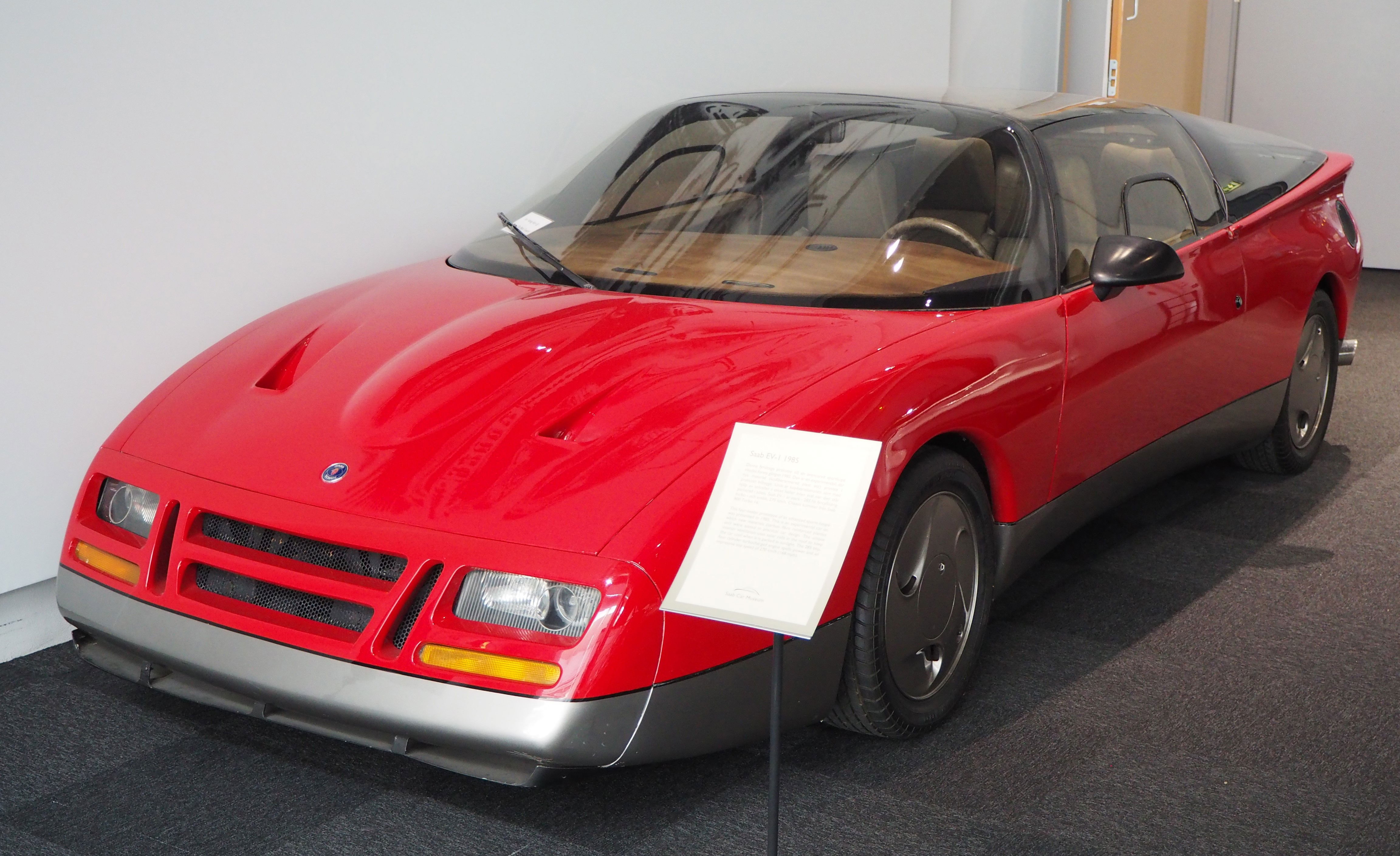

Saab EV-1 (1985) – The Electric Saab That Predated GM’s EV1

Why it mattered: A decade before GM’s infamous EV1, Saab built a practical electric hatchback with regenerative braking and a 120-mile range, impressive for the 1980s. It even had a solar panel roof to assist charging.

Why it failed: Battery tech was still primitive (lead-acid cells), and Saab’s financial struggles killed further development.

What could have been: If Saab had pushed forward, they could have been the Tesla of the 1990s.

Renault Étoile Filante (1956) – The 191 MPH Gas Turbine Land Rocket

Why it mattered: This French streamliner, powered by a helicopter turbine, set a 191 mph record in 1956, proving turbines could be viable for high-speed cars. It was more advanced than Chrysler’s later Turbine Car.

Why it failed: Renault had no interest in production, and turbine engines were too thirsty for everyday use.

What could have been: If developed further, it could have led to a French-led turbine performance revolution, possibly influencing Le Mans or Formula 1.

Honda HP-X (1984) – The Mid-Engine, 4WS Prelude That Never Was

Why it mattered: This prototype was a mid-engine Prelude with four-wheel steering, active suspension, and a futuristic cockpit. It was Honda’s vision of a cutting-edge sports car, blending F1 tech with everyday usability.

Why it failed: Honda feared it was too radical for mainstream buyers and stuck with front-wheel drive.

What could have been: If produced, it could have redefined Honda as a true sports car rival to Porsche in the 1990s.

GM Sunraycer (1987) – The Solar Car That Outraced Everything

Why it mattered: Before the Prius or Tesla, GM built this solar-electric racer, which crushed the competition in the 1987 World Solar Challenge, averaging 41.6 mph across 1,950 miles of Australian outback—using less energy than a hair dryer. It proved solar-hybrid tech was viable decades before it became trendy.

Why it failed: GM shelved the tech to focus on SUVs and internal combustion. The program’s lead engineer, Alan Cocconi, later founded AC Propulsion, which inspired Tesla’s early drivetrains.

What could have been: If GM had pursued solar-assisted EVs, they could have dominated sustainable mobility before Elon Musk even started Zip2.

BMW Just 4/2 (1995) – The Carbon Fiber City Car Ahead of Its Time

Why it mattered: This tiny two-seater was 100% carbon fiber, weighed just 1,300 lbs, and had a modular design allowing for different body styles. BMW called it "the car of the future." It was a precursor to the i3 and i8.

Why it failed: In the 1990s, carbon fiber was too expensive for mass production, and BMW prioritized conventional models.

What could have been: If BMW had cracked cost-effective CFRP production earlier, lightweight urban EVs might have arrived a decade sooner.

Dymaxion Car (1933) – Buckminster Fuller’s Three-Wheeled Revolution

Why it mattered: Designed by futurist Buckminster Fuller, this teardrop-shaped, rear-steering 3-wheeler could seat 11, hit 90 mph, and get 30 mpg. This is unheard of in the 1930s. Its aerodynamic design was decades ahead of its time.

Why it failed: A fatal crash (caused by another driver) scared off investors, and Fuller’s unorthodox steering made it tricky to handle.

What could have been: If perfected, the Dymaxion could have redefined car design in the 1940s, making streamlined, fuel-efficient vehicles the norm.

NSU Ro 80 (1967) – The Wankel-Powered Sedan That Almost Beat Mercedes

Why it mattered: This German luxury sedan had a twin-rotor Wankel engine, semi-automatic transmission, and wind-tunnel-tuned aerodynamics. It was named Car of the Year in 1968 and drove like a spaceship compared to rivals.

Why it failed: Rotary engines wore out quickly, and NSU’s fix bankrupted the company (leading to its absorption by Audi).

What could have been: If Mazda-style reliability fixes had come sooner, the Wankel could have rivaled piston engines, making smoother, lighter powertrains mainstream.

Leyland-BMC 1100 Hydragas (1962) – The British Suspension That Could Have Beaten Citroën

Why it mattered: This prototype used Hydragas suspension (a fluid-based system superior to hydraulics) for an ultra-smooth ride. It was more durable than Citroën’s complex hydropneumatic setup but just as comfortable.

Why it failed: British Leyland’s financial chaos killed innovation, and the tech was only used in niche models like the Austin Allegro.

What could have been: If widely adopted, Hydragas could have made luxury-car ride quality affordable in everyday vehicles.

Ford Nucleon (1958) – The Atomic-Powered Car That Never Was

Why it mattered: Imagine a car that never needed refueling. The Nucleon was designed around a miniature nuclear reactor, using uranium fission to power a steam turbine. Ford estimated it could go 5,000 miles per "fill-up"—making gas stations obsolete.

Why it failed: Radiation shielding was impossibly heavy (and dangerous). The public (rightly) feared nuclear accidents in traffic, and Cold War tensions made uranium too politically sensitive.

What could have been: If nuclear tech had been miniaturized safely, we might have had zero-emission cars decades before EVs. Instead, the Nucleon remains a retro-futuristic icon.

Chrysler Turbine Car (1963) – The Jet-Engine Sedan You Could Actually Drive

Why it mattered: Chrysler built 55 working prototypes of this bronze-colored coupe, powered by a turbine engine that could run on gasoline, diesel, kerosene, or even tequila. It was smoother, simpler, and more durable than piston engines.

Why it failed: Throttle lag made city driving jerky, and fuel economy was terrible at low speeds. Ultimately, emissions regulations (coming in the 1970s) doomed turbines.

What could have been: If Chrysler had cracked the efficiency puzzle, we might be filling up with jet fuel today. Most surviving models are in museums. Jay Leno owns one.

General Motors Firebird I-III (1953–1959) – The Fighter Jet-Inspired Dream Machines

Why it mattered: This trio of concepts (Firebird I, II, and III) looked like land-bound fighter jets, featuring titanium bodies, guided "autopilot" systems, and even turbine power. The Firebird III (1959) had seven (!) computers and joystick steering.

Why it failed: The concepts were too expensive for production, and it didn’t help that turbine were impractical (see Chrysler’s struggles). The public wasn’t ready for spaceship cars, either.

What could have been: If GM had scaled down the tech, we might have had autonomous, computer-controlled cars by the 1980s.

Volkswagen EA 266 (1969) – The Backwards, Air-Cooled Hybrid

Why it mattered: VW’s secret prototype had a rear-mounted, water-cooled inline-4 (heresy for air-cooled Beetle fans) and a hybrid-electric system. The engine was under the rear seats, freeing up cargo space.

Why it failed: This prototype’s design proved too complex compared to the Beetle. The 1973 oil crisis forced VW to shift its focus to the Golf, and VW’s engineers feared carbon monoxide leaks into the cabin.

What could have been: If released, the EA 266 could have made VW a hybrid leader—40 years before the Prius.

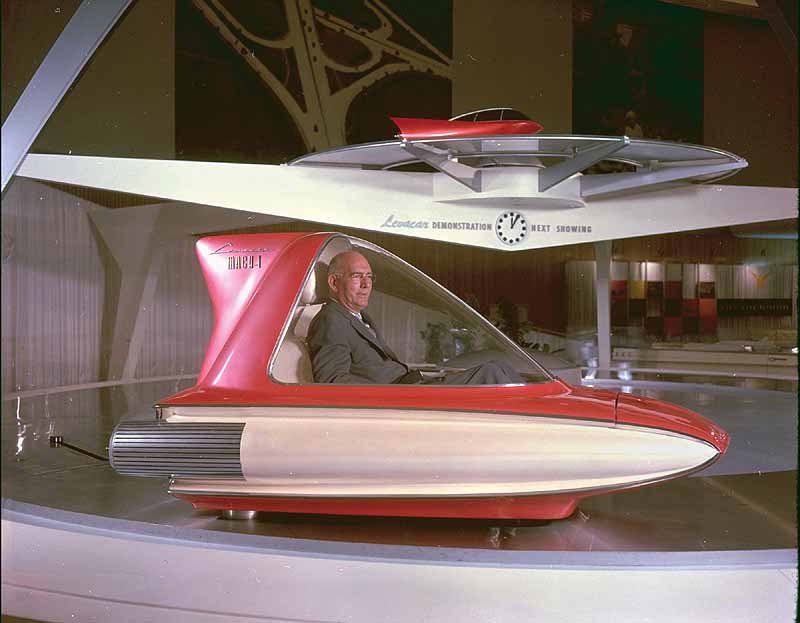

Ford Levacar Mach 1 (1959) – The Hovercar That Defied Physics

Why it mattered: Ford’s concept floated on a cushion of air, like a hovercraft. It was designed for frictionless travel, with theoretical speeds up to 500 mph. The military even took interest for hover-tank research.

Why it failed: Ford couldn’t find a practical way to stabilize the Levacar at high speeds. Energy demands were insane (like a helicopter, but worse), and the 1960s materials science couldn’t make the concept viable.

What could have been: If maglev or air-cushion tech had advanced, highways might look like "The Jetsons" by now.

The Ultimate Twist

GM Firebird III.

Many "failed" prototypes eventually succeeded in disguise: - The Firebird’s joystick steering returned in the 2024 Tesla Cybertruck. - The EA 266’s layout inspired the Bollinger electric trucks. - The Turbine Car’s multi-fuel engine lives on in military vehicles. So the next time you see a futuristic concept car, ask: "Is this today’s Levacar—or tomorrow’s Tesla?"

Honorable Mentions (Because Twenty Isn’t Enough)

- Alfa Romeo Scarabeo (1966): A mid-engine, wedge-shaped prototype that inspired the Lamborghini Espada but was deemed too extreme.

- Mazda MX-02 (1983): A digital-heavy, turbo-diesel, four-wheel-steering concept with a voice-controlled AI assistant (in 1983!).

- Ferrari Modulo (1970): A spaceship-like concept with full-width sliding cockpit—Pininfarina’s wildest design, never produced due to impracticality.

- Volvo VESC (1972): A crash-safe prototype with airbags, ABS, and crumple zones years before they were standard.

- Mazda MX-81 (1981): A wedge-shaped, digital-dash concept with a retractable steering wheel, hinting at autonomous driving.

- Jaguar XJ13 (1966): A V12 Le Mans prototype so advanced that Jaguar shelved it to avoid disrupting their sedan sales.

Note:

The Mazda MX-81 and Mazda MX-02 are distinct concept cars that shared the MX designation. Debuting in 1981 at the Tokyo Motor Show and designed by Bertone, the MX-81 Aria featured a wedge-shaped compact design, pop-up headlights, and a futuristic interior with TV screens and a rectangular steering wheel.

The MX-02, on the other hand, was introduced two years later in 1983 as a five-door hatchback with large windows, aerodynamic rear wheel covers, and flared-in door mirrors. It also had rear-wheel steering and a head-up display, making it a more advanced concept in terms of technology.

The Big Takeaway

These prototypes are some of the most radical "what if?" stories in automotive history, each one pushing boundaries so far that they still feel futuristic today. Many were victims of bad timing, corporate caution, or technological limitations. But their ideas eventually resurfaced in modern vehicles.

They represent missed opportunities that could have accelerated tech like hybrids, lightweight materials, and alternative engines by decades. The auto industry’s conservatism (and occasional bad luck) kept them buried, but their DNA lives on in today’s cars. The real question is: How much further ahead would we be if even one of these had succeeded?