The Gas-Powered Elephant in GM's $4 Billion 'Electric' Room

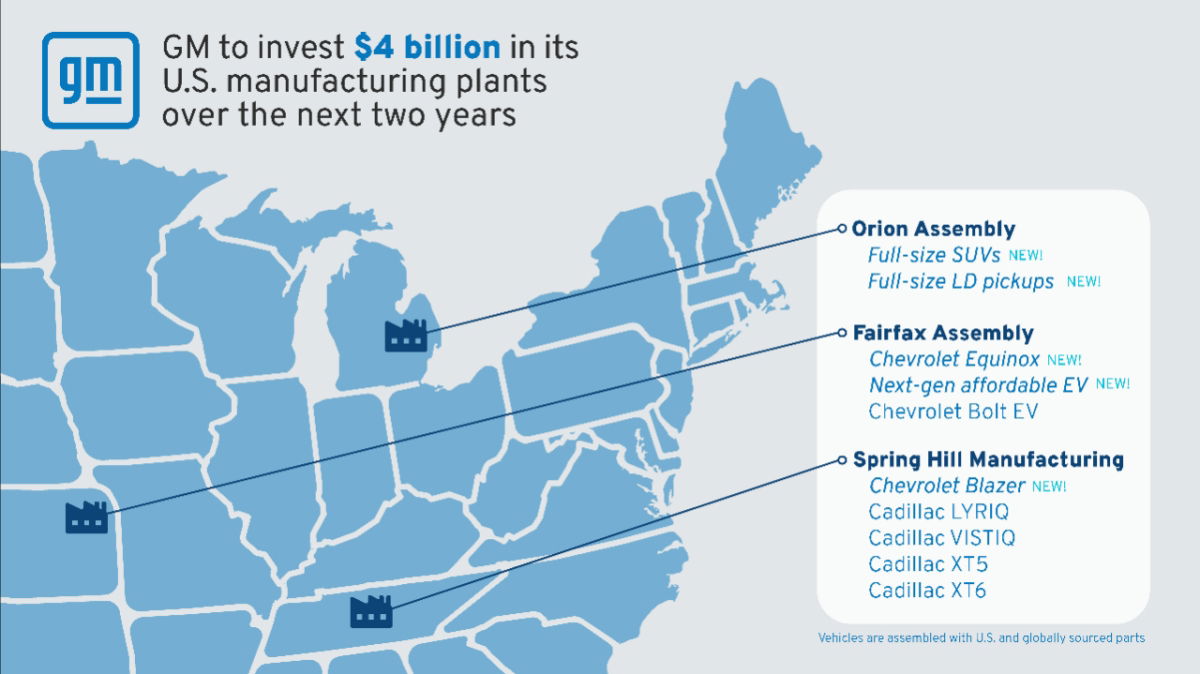

General Motors has framed its $4 billion investment in its Orion Assembly and Lansing plants, announced on June 11, 2025, as a bold step toward an electrified future. But beneath the polished press releases and political applause lies a far more revealing story; one of retreat, recalibration, and a tacit admission that the auto industry’s breakneck shift to electric vehicles has hit a wall.

GM’s relationship with electric vehicles is fraught with false starts. In 1996, the company launched the EV1, the first modern electric car designed for mass markets, only to cancel the program in 2003, citing high costs and limited demand.

Two decades later, CEO Mary Barra pledged to phase out gasoline vehicles by 2035, declaring EVs a "top strategic priority". Yet the Orion plant’s pivot back to gas-powered trucks mirrors the EV1’s demise, a pattern of bold rhetoric followed by pragmatic retreat when market realities bite.

See also:

A Numbers Game

The shift is rooted in GM’s precarious financial balancing act. While the company projects optimism about EV profitability "nearing the crossover point", its 2024 financials reveal deeper struggles: a net income drop from $10.1B to $6.0B year-over-year.

The drop was primarily driven by $4B in non-cash restructuring charges and impairments related to its China joint ventures, as well as $0.5 billion from halting funding for its Cruise robotaxi business.

GM maintains a positive outlook despite these setbacks. EV sales, though growing (GM is now the #2 U.S. seller behind Tesla), contribute just 9% of total revenue. Meanwhile, gas-powered trucks and SUVs, which account for 70% of GM’s U.S. sales, generate the margins funding its EV ambitions.

"GM is trying to be two companies at once," says auto analyst John Dixon, who has tracked GM’s EV strategy since the 2020s. "They’re touting battery breakthroughs while quietly doubling down on V-8 engines because that’s what pays the bills today".

This duality is evident in GM’s capital allocation: $888 million for next-gen V8 engines in Tonawanda versus $2.3B for its Spring Hill battery plant—a lopsided bet on the present over the future.

The Broken Promise Of An All-Electric Future

Just three years ago, GM CEO Mary Barra stood before investors and pledged that the company would phase out gasoline-powered vehicles entirely by 2035. The Orion Assembly plant in Michigan was supposed to be a cornerstone of that vision, retooled exclusively for electric Silverados and GMC Sierras.

But in a stunning reversal, GM confirmed that Orion will now produce gas-powered Chevrolet Silverados and GMC Sierras by 2027, a clear signal that the company no longer believes an all-electric future is imminent. Industry analysts would be right to point to slowing EV demand as the primary culprit.

Despite GM’s status as the second-largest EV seller in the U.S., behind only Tesla, growth has plateaued. Rising interest rates, persistent charging infrastructure gaps, and consumer skepticism have forced automakers to reassess their strategies.

GM’s decision to retrofit Orion for gas trucks—while still maintaining some EV production—reveals a hedging strategy rather than a full commitment to electrification. The timing of GM’s announcement is hardly a coincidence.

Just weeks before, President Donald Trump rolled back California’s 2035 zero-emission vehicle mandate, a move that effectively neutered one of the strongest regulatory drivers for EV adoption. GM CEO Mary Barra had recently met with Trump, and the company’s sudden shift toward gas-powered production aligns suspiciously well with the former president’s pro-fossil fuel policies.

The White House will frame GM’s investment as a win for American manufacturing, with press secretary Karoline Leavitt praising the move as evidence of the administration’s "commitment to U.S. jobs."

But the reality is more nuanced.

By shifting production of the Chevrolet Blazer and Equinox from Mexico to Michigan, GM is also responding to Trump’s 25% auto tariffs policy designed to pressure automakers into domestic manufacturing. The company’s emphasis on "American jobs" in its press release is as much about political survival as it is about economic strategy.

“We believe the future of transportation will be driven by American innovation and manufacturing expertise,” said Mary Barra. “Today’s announcement demonstrates our ongoing commitment to build vehicles in the U.S and to support American jobs. We're focused on giving customers choice and offering a broad range of vehicles they love.”

If the UAW welcomes GM’s investment, it obscures tensions beneath the surface. It would mean that while the union celebrates "American jobs," GM’s 2024 restructuring included $4B in non-cash charges tied to plant consolidations.

The Orion shift avoids new job creation, instead reallocating existing union labor from EVs to gas vehicles, a stopgap solution that risks future clashes as EV adoption accelerates.

Battery Breakthroughs vs. Gas-Powered Profits

GM has not abandoned its electric ambitions entirely. The company continues to tout its next-generation LMR (lithium-manganese-rich) batteries, promising battery pack costs reduction by around $30 per kilowatt-hour by 2028.

GM, in partnership with LG Energy Solution, plans to begin commercial production of LMR batteries by 2028. The LMR chemistry uses more manganese and less cobalt and nickel, which significantly reduces material costs while maintaining high energy density.

But the fine print reveals a stark contradiction: while GM invests in future battery tech, it is simultaneously pouring $888 million into its Flint Engine plant to ramp up production of its sixth-generation small-block V8 engines. This dual-track approach underscores a fundamental tension in the auto industry.

Electric vehicles may be the future, but internal combustion engines remain the profit engine of today. Gas-powered trucks and SUVs still account for the vast majority of GM’s earnings, and with EV margins under pressure, the company cannot afford to abandon its cash cows.

While GM hedges, competitors are making bolder moves. Tesla’s Cybertruck and Ford’s F-150 Lightning dominate the electric pickup segment, forcing GM to discount the Silverado EV.

Meanwhile, Chinese automakers like BYD, with a 24.1 forward P/E ratio compared to GM’s 5.75, are leveraging state subsidies and vertical integration to undercut GM on price. "China’s EV market is already 35% electrified; GM is playing catch-up globally," warns Dixon.

GM’s Ultium Cells joint venture aims to produce 30GWh annually in Lordstown, Ohio, enough for ~300,000 EVs. But with Tesla producing 100GWh at Gigafactory Nevada alone, GM’s scale remains inadequate for mass-market EVs. "They’re betting on LMR batteries to leapfrog competitors, but until then, gas trucks fund the R&D," notes Dixon.

Labor, Tariffs, And The Hidden Costs Of Transition

The United Auto Workers (UAW) union publicly praised GM’s investment, calling it a victory for American workers.

In response to GM’s announcement of $4 billion in new investments in facilities in Michigan, Kansas, and Tennessee, UAW President Shawn Fain called it a “major victory,” emphasizing that it reflects the union’s long-standing push to rebuild American manufacturing and protect union jobs.

UAW Vice President Mike Booth also highlighted that these investments show GM is “reinvesting in the union workforce that makes it all possible,” crediting skilled UAW members for GM’s profitability.

The union framed the move as a turning point in reversing decades of offshoring and as a validation of their advocacy for stronger trade policies and domestic job creation. But the announcement included no new job commitments beyond previously agreed-upon terms in the 2023 labor contract.

Instead, the move appears to be a strategic appeasement of the UAW, which has been vocal about protecting jobs in an uncertain transition to electrification.

Meanwhile, Mexican officials insist that no jobs will be lost at their plants despite GM’s decision to shift Blazer and Equinox production to the U.S. But industry insiders see this as a temporary reassurance, one that could change if tariffs remain high and automakers continue reshoring production.

GM’s capital expenditures tell the story of a company stretched thin. With annual spending between $10 billion and $12 billion through 2027, the automaker is juggling EV development, gas vehicle refreshes, and tariff-related supply chain shifts, all while free cash flow per share remains deep in negative territory at -$5.36.

Despite $23.7B in cash reserves, GM’s automotive free cash flow is projected to drop to $11B–$13B in 2025, squeezed by $10B–$12B in annual capital expenditures. "They’re burning cash on dual platforms—EV R&D and ICE refreshes—without the margins Tesla enjoys," says a Wall Street analyst who requested anonymity.

The company’s leadership insists it is "well-positioned" for the future, but the numbers suggest a precarious balancing act. GM’s stock has underperformed compared to pure-play EV competitors, reflecting investor skepticism about its ability to navigate the transition.

Tesla’s stock surged over 100% in 2023, driven by investor enthusiasm around AI, self-driving tech, and charging network dominance. BYD, China’s EV powerhouse, also saw strong gains, fueled by record-breaking sales and global expansion.

In contrast, GM’s stock rose more modestly, with a 32% gain in 2024—respectable, but still trailing the explosive growth of its EV-focused rivals.

This underperformance reflects investor caution around GM’s dual-track strategy of balancing legacy internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles with its EV transition, while pure-play EV makers are seen as more focused growth stories.

GM’s stock trades at a 71% discount to sector median P/E, reflecting doubts about its transition. While share buybacks ($5B since 2024) buoy short-term confidence, long-term investors question whether GM can achieve its 2035 target without alienating its gas-powered base.

The Bigger Picture: An Industry At A Crossroads

GM’s retreat mirrors broader industry hesitancy. Ford has similarly dialed back its EV investments, and even Tesla has warned of "notably lower" growth in 2025.

The auto industry, once racing toward an electric future, is now hitting the brakes, not because the technology has failed, but because the market isn’t moving as fast as regulators and executives had hoped.

The EV1’s failure in 2003 was blamed on high costs and weak demand, the same challenges GM faces today. But this time, climate regulations and Chinese competition leave no room for retreat. "GM is trapped between its past and future," concludes Dixon. "The Orion pivot isn’t just a delay—it’s a referendum on whether legacy automakers can survive disruption".

The real story behind GM’s $4 billion investment is not about innovation or job creation. It’s about survival. The company is walking a tightrope between political pressures, financial realities, and an uncertain market. And for now, at least, gasoline still holds the winning hand.